Not too long ago, I was just like many social media users. I’d see tons of stories describing people catfishing, being catfished and worst of all, ‘Tinder Swindling’.

A catfish, for those who don’t have the term etched in their minds thanks to MTV’s hit show, is someone who takes on a fake identity using others’ photos and videos to create some kind of relationship. Catfishing antics vary in motive. Some do it for love, others for money and others for their version of a good laugh.

I’d usually feel a fleeting sense of sympathy for the stories I’d read about people who had been catfished. In the case of the actual Tinder Swindler as seen on Netflix, I felt boatloads of empathy for the people allegedly conned by Simon Leviev.

I’ll admit, I’d usually wonder how many of the victims in other stories didn’t pick up on those blazing red flags. Especially after the person refused to meet the “love of their lives” face to face for the most creative reasons ( par the Leviev cases, Simon really played the game to a tee).

However, I never really considered what it felt like to be the person who’d been used unknowingly in the catfish’s game – until it happened to me.

On a day like any other, I realised something was off when I was receiving an unusual amount of Direct Message requests on Instagram. My first thought was that I’d maybe posted an embarrassing photo of myself accidentally.

Was it one of those silly face selfies I’d usually send to a close friend? Maybe it was a photo of me devouring pasta awkwardly in celebrating budding cooking skills. Nothing that couldn’t be laughed off, right?

Realising that most of the DMs were from foreign men, something was fishier than Kalk Bay’s Harbour. People I had no mutual followers with were asking me how I was, as if we’d already spoken.

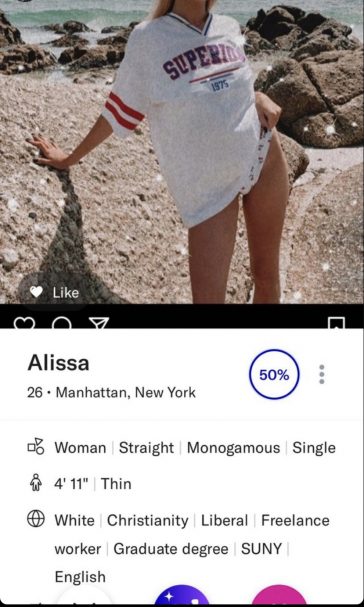

One user finally let me in on the inside joke. “So, I’m assuming this isn’t you right?” before sending me screenshots of myself on a dating app I’d never even heard of, Plenty of Fish.

There it was – my photo above the name Alissa who apparently lived in New York. The closest thing to New York that the actual girl in the photo was used to, was NY Slice.

Soon, I received other screenshots from different people using different dating apps enquiring about me. How they found my actual Instagram is still a mystery, but alas, there we stood.

I learned that the person pretending to be me went by variations of ‘Alissa’, and in another scheme, they’d sold their character as a graphic designer who was “looking for [their] future husband.”

My first reaction was shock (and a little laughter). I was in a relationship and didn’t have any dating apps.

It was pretty obvious that my pictures had been stolen from Instagram, and the rest of Alissa’s ‘biography’ was nothing more than a creative writing project (an anti-climactic one, at that. They could’ve at least made her a crime-fighting pilot or something).

Then, things got worse, as they often do in these situations.

Alissa had been scheming or attempting to scheme these people for money. I’m not sure how many, or how much was banked, but another user shared screenshots with me of a WhatsApp number that had capitalised on my photograph, asking for money to help their “sick mother” who they claimed had Leukaemia.

The only person who felt sick was me. The story was bogus, playing on a made-up travesty. But a little sleuthing led me to a plan of action that might just help you too if you’re ever in these uncomfortable shoes:

What you need to know if your photos have been stolen and used in a catfishing scheme

Raise the alarms

Alert your followers, change your bio to “only account” if someone’s stolen your pics to create a new Instagram account and let anyone who’s contacted you know that they’ve been catfished (just without the ‘bamboozled tone). Ask your friends to share the fake news too. Chances are, if people are using your page to farm photos, they’ll quit when they know you’re onto them.

Report fast and furiously

Admittedly, ‘furiously’ isn’t always necessary. But reporting is. Find the apps that these photos are circulating on and let them know what’s happened. Pro-tip: If you don’t get a response, tag the dating apps’ social media accounts on a social media post or story of your own, and you’ll get feedback quickly as social media managers start sweating.

You can get accounts banned, and you can ask them to block the number or email from making new accounts too. However, the deep-sigh moment comes in that people can make new accounts with new numbers or emails. In that case, you just have to keep your finger on the pulse (see the next step).

Reverse Image Searching

To check if you’ve been catfished, or if people have made any new accounts with your pictures, do a quick reverse image search. There are different apps you can use (like TinEye) or you can use Google itself (click the camera icon under the Images tab on Google).

You can take the authorities-route, but it’s complicated

You might imagine a scenario like this:

“Police, help my photographs have been stolen!”

(Phone gets put down immediately).

You probably know by now that the biggest hurdle when it comes to cybercrimes is that there isn’t exactly a clear definition for many of them. Last year, the South African government focused on legislation related to the cyber sphere that would allow SAPs to go ahead with more domestic investigations, but there’s the catch. Domestic.

What happens when the people who stole your photos are overseas? What if you don’t know where they are?

The reality is that law enforcement bodies across the world are still (unfortunately) finding their feet in the digital space, especially for ‘petty’ crimes. You can’t exactly call Interpol directly for a case like this, (you can get to their cybercrime departments, but you’ve got to go through your local police) and then of course the process becomes a lengthy one.

You also need to be sure of what you’re reporting. It’s not technically theft of your photos if you upload them to Instagram, because then your pictures belong to Instagram. It’s not an impersonation, because the perpetrators have created a new character. It may be swindling, but if the people willingly gave money to someone else, it’s a pretty sticky legal situation, especially if you don’t know who they gave money to. What it is inarguably for most people, is catfishing, which has typically been a contested debate over whether it’s a crime or not.

Unfortunately, the procedures to bring cybercriminals to book is still a highly complex one. It doesn’t mean you can’t take this route. Depending on the intensity of your case, you should. Make sure you’ve got evidence, have already reported it to the platforms, and try to find out as much supporting information as you can when you go to the authorities.

The good and the annoying news

So many of my friends have had to share “Not Me” captions alongside screenshots of fake accounts. Something so absurd has become normalised and desensitised to the point where we just accept that this is what happens in the digital space.

The annoying news is that I can’t tell you with absolute certainty how to stop this from happening (unless you live under a rock, which actually seemed attractive at one point). The good news, is that I can tell you how to feel a little better about it all.

- Don’t take on the guilt for something you didn’t do!

- Don’t feel like you can never post anything on social media ever again. It might take a while to get over the anxiety of it all, but your social media should still be a place for you to enjoy.

- Make your account private if you can, or make a finsta (fake Instagram account). Finstas have become the new space for people to share their memories in less curated way. Make it private and only allows follows from your trusted nearest and dearest.

- Don’t feel ashamed! So you posted a photo in your bikini and now you’re being used as a catfish. Should you feel ashamed? Absolutely not. Someone could’ve just as easily capitalised on your content if you were wearing a T-shirt.

- Understand the demographics: Psychology Today shares that women are more likely to be catfished (ie: be the victim of a scheme) after a case study recorded that men are more-so associated with relationship initiating. So lads, you’re not exempt from being used in a catfish’s plans either.

- Make like The Beatles and let it be. The personal discomfort isn’t something you should carry around with you.

At the end of the day, and as it is with so many things in our lives, it’s not about what happens but how we handle them – the magnitude is irrelevant.

And, if you’re on the other side of a catfishing scheme and something smells off about a person online, please trust that ‘off’ feeling in your gut. There are red, orange and green lights when it comes to meeting people online (and in person), and a major red flag in either scenario is someone asking you for money when they hardly know you.

You don’t want to be with someone asking you for cash so quickly in the first place, and you definitely don’t want to be fuelling a scheme.

ALSO SEE:

Why Netflix is being sued by the real Rachel from ‘Inventing Anna’

Feature Image: Pinterest