I grew up with social media – like much of my generation – in the most literal sense.

As we matured, so did the socials. In some odd ways we raised them. In others, they raised us – like a bunch of kids preparing each other for life.

Unlike millennials who saw the rise (and fall) of platforms in their more mature teens, social media became a part of Gen Z’s daily vocabulary at a tender age. I learned how to do my first makeup looks from YouTube. Snapchat was the local news broadcaster – always keeping everyone in the loop of what our friends were up to, as cringeworthy as it sometimes was. I learned to laugh at my periods through Vine, and Instagram taught me the power of first impressions.

Welcome to the playground

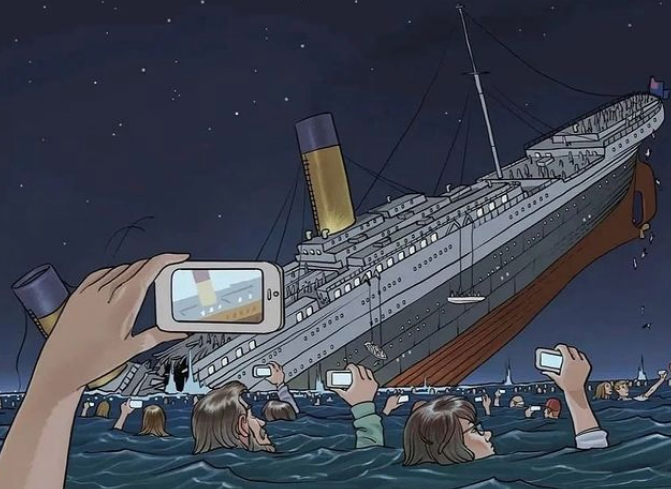

Almost 10 years ago now, social media was like a playground without chaperones, where everyone followed the leader, played tag religiously with @ signs like status symbols, and never questioned whether the scars and bruises from falling down a couple of times would matter in the future.

Fast forward to today, and that playground has become something out of Architectural Digest. There are formulas to everything that was once carefree creativity, we know exactly what to feed the algorithms and although we’ve aged, gotten jobs and progressed in all the traditional senses, we’re still following the leader as much as we study her.

I followed the leader so far down the rabbit hole that I wrote an entire thesis on social media in diplomacy. For those who still think social media is an airy fairy concept – believe me, it’s part of every organisation and company’s boardroom meetings.

My research was one of the first times I realised how much it had shaped all of us. How was all this consumption shaping us in those early days? How had our minds absorbed it? Who were we as a result, and who would we have been without it?

In 2016, Mark Miller, a philosopher of cognition published an essay titled ‘The Warped Self’. Miller was part of the group that shared the addictive, depressive and anxious relationships we have with socials, and argued that “as long as it remains the case that more engagement means more profit, then designers of social media will have a de facto interest in implementing designs that lead to human misery.” Not exactly a happy filtered picture.

A more recent study led by Dr. Twnge to look at teens in the U.S and U.K. It drew the conclusion that the relationship between social media and users (female users particularly) was impacting mental health in a worse way than binge drinking and hard drugs – reality check? My eyebrows raised to the roof.

In the past five years, there have been countless studies on social media’s impact on our mental realms. We know them, we understand them, but as we do with so many elements of our well-being, we often shrug off what doesn’t suit us.

Cue the Mental Health Movement

The pandemic changed everything, and its star pupil was TikTok which made it’s bold entrance turning from ‘niche platform’ to king of the castle.

Suddenly, life as a highlight reel was exchanged for a little more honesty. Struggle turned into self-love and betterment.

A movement toward mental health awareness had become more accessible as people started sharing their inner conversations all over the internet. It wasn’t just refreshing – it was the hydration we all needed, especially in those months of isolation – but too much water cannot make the flowers grow.

The concern would only come later as people eventually realised that we were over-self-diagnosing, hyperfixating on topics without professional and personal input, and overconsuming still. We all discussed the problems with social media in a more open way, but we were still playing into its clutches. Almost as if Mac Donalds was telling us to eat healthier and had a support group for all people who were addicted to its food.

So what do we do with all this information?

Whether we subscribe to it or not, we live in the age of attention.

How we interact on the playground is up to us; we have the freedom to pick where we place our attention and how often. With mental health at the forefront of conversations, we owe it to each other (and to ourselves) to act on both mindful consumption and creation, not unlike sustainable dreams – let less be the best.

ALSO SEE:

Feature Image: Pierre Brignaud