Tumi Morake modelled her public persona on her mother, a charming and contentious woman who used her big, bold voice to say what others were afraid to utter.

By 2003, I was deeply in debt to the university. I had applied twice already for a loan from Wits, and had now run out of lifelines. I did not even have enough to register for a new year, even if I could raise the money I owed. Eventually I received a letter saying I would not receive my results or be readmitted until I had paid my debt. I had seen it coming, but it still left me demoralised. I could not come this close to my degree and have the opportunity snatched so easily from me. I wanted to do this one thing for myself and my mother.

What it took, in the end, was six years of building a career and making a life for myself forged from blind determination and an insatiable hunger to make a success of myself. In 2009, after giving birth to my first child, I decided to tie up loose ends. I had repaid my debt to Wits and had a small window of opportunity to go back and complete my degree. I did not need to go back for the skills; I wanted to finish the degree for my mother, so she could say she had a graduate in the family. I wanted to gift my mother this degree. She had loved my overconfidence in applying to a single university, and I had to deliver. My first day was daunting. You could smell the ‘the world is yours’ promise in the air. But I felt my age. The fashion,lingo and energy of the campus made me feel old. I sat in class with 20-year-olds with idealistic views of the industry they were about to be thrust into. It was wonderful to go back to basics, to interrogate my work. I was studying the world I was working in and thinking critically about it.

Robust conversations around representation and narrative agency gave my brain the wake-up call it needed. The cobwebs and dust were cleared off my academic mind. Then I found my voice. I drove my stand-up comedy to the limit. If comedy thrived on society’s dark corners and grey areas, then it could be a channel for demystifying the very taboos that feed oppressive systems. I wrote a stand-u special based on menstruation. The piece would need to challenge, to speak back. It also had to be funny. Guys, I wrote an essay on menstruation. If I wasn’t so hungry for success, I would have registered for my masters to further explore this thing. I identified my political position as a black female comedian over the months that I worked on this project. Whether I do it consciously or not, my identity politicises my comedy. This realisation was the most exciting part of going back to school. I got to put myself and my career path under a microscope. It was not without its challenges. My mother was not doing any better, and her ill health was taking an emotional toll on me. In the end I passed, and when my letter of graduation arrived, I took it to Mama with the delight of a schoolkid.

Her first graduate. Normally she would not have missed my graduation for the world, but by the time it occurred in 2011, she had already been hospitalised. She had been looking forward to this day ever since I told her I had finally completed the damn thing, and I could tell that she was heartbroken to miss it. Her health had deteriorated to the point where I was begging God to at least let her see me do this one thing, so I was very emotional at the ceremony. My usual chattiness was gone. Graduating just did not carry the same meaning without my mother there. I fought back tears when my name was called, and I walked across that stage without hearing my mother cheer me on.

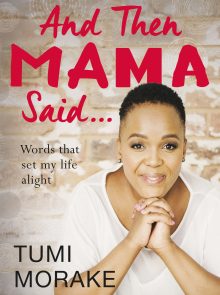

AND THEN MAMA SAID BY TUMI MORAKE

Published by Penguin Random House

ALSO SEE BOOK CLUB: TOP 9 BOOKS OF THE MONTH

[Features image via Pexels]